With Courage But No Cover

- Claire Jordan

- Jun 21, 2022

- 4 min read

To me, no #CWGC headstone is ever just another grave.

Each one is tangible evidence of a once living, breathing, brave man.

His end doesn’t define who he was in life; that headstone showing name, rank and number doesn’t hold down or obliterate his character, the people who loved him, his favourite tobacco, his football team, his pet dog.

If we look hard enough, we can still find something of who he was, and honour him for it.

This unassuming grave in the grand amphitheatre of the ancient military cemetery at Shorncliffe on the Kent coast above Folkestone belongs to Ernie Savatard.

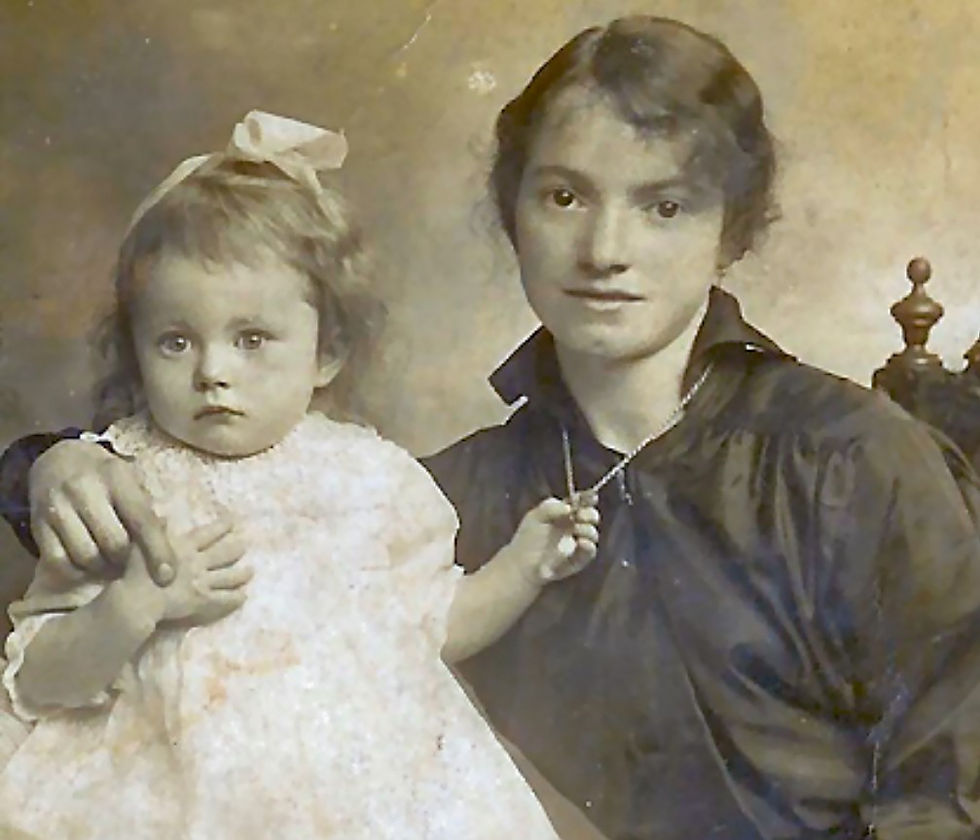

He was born in Birmingham to an older father on his second marriage; by the time Ernie had saved his pennies, made the bold decision to emigrate to Canada in search of a different life and boarded the White Star Line steamer which took him, all alone, to Halifax in September 1910, his Mum was already gone and his father was not long for this world.

By the spring of 1915 when he volunteered to fight, Ernie had made a good life for himself in Winnipeg as a butcher. He had yet to marry.

He fibs about his age to make sure he gets in (perhaps aware he looked older than he is) and he's described on enlistment as having dark blue eyes, a dark complexion and “hair: black (slightly grey)”.

Which, in another place on his papers is miss-transcribed as “Hair: black (slightly bald),” an unnecessary indignity about which we hope he never knew.

Ernie embarks for old England once more on 11th September 1915, five years since he left and, after training, is sent to France with 8th Canadian Infantry Battalion before Christmas.

Exactly one year after he sails from Montreal, he is on the Somme with his Battalion, holding down the line in a Mouquet Farm subsector.

‘Mucky Farm’ to the Tommies and ‘Moo Cow Farm’ to the Aussies who fought there, it was a truly terrible place, the stuff of nightmares: a heavily fortified enemy position on a ridge which ran north-west across the battlefield from the infamous village of Pozieres.

The farm buildings were rubble, but it had extensive underground cellars which had been reinforced and fortified by the Germans.

Trying to take Mucky Farm was really an earlier, unending version of what we would face on the Normandy beaches on 6th June 1944; we had to attack up an incline towards a heavily-defended enemy position, in full view of many machine-guns and snipers untouched by our bombardments, with courage but no cover.

When Ernie’s Battalion came to this awful place, the Battle of the Somme had been going for ten weeks and during that time, the farm had been unsuccessfully attacked nine separate times by three valiant Australian Divisions, costing over 11 000 casualties.

When Ernie went into the trenches on 7th September, the Operational Orders stated that each man must be carrying: “2 days’ rations, a filled water bottle, iron ration, 2 bombs, 120 rounds small arms ammunition, 2 sandbags.”

And this was such a sticky sector that they would only be obliged to hold the line here for 48 hours before being relieved.

Ernie, with his filled water bottle and his two sandbags, stuck it out for the 48 hours, as he had already stuck out countless other periods in the line during the ten months he’d been in France, but none before in quite as horrendous a place as this, strewn still as it was, with the dead of 1st July who’d lain uncollected in the summer heat ever since.

On 9th September, they were relieved in the line and moved back to support dug-outs at La Boiselle, really only a matter of a mile and a half, and hardly any safer than they had been at Mucky Farm.

‘Relief’, I think, is a relative term at this point.

So here they were on 11th September, at their backs the gigantic crater caused by the mine we’d blown on 1st July, which had inadvertently in that instant broken the shin bones of the first three hundred of our own boys closest to the blast, legs braced against the fire-step, waiting to go over the top when the whistles blew.

“Weather fine,” says the 8th Canadian Infantry Battalion war diary. “During the afternoon, the enemy shelled vicinity of Battalion… 1 casualty.”

This one casualty is our Ernie Savatard.

He’s hit by shrapnel in the chest, which breaks his ribs.

He is medically evacuated back to Boulogne and then to a military hospital in Leeds, where he is patched up, his broken ribs mercifully not puncturing his lungs, and his bruises and fractures begin with agonising sluggishness to heal.

A month later, out of danger (in a manner of speaking), he is transferred to a Convalescent Hospital at Epsom; by Christmas, he’s cleared for depot duty, and sent to the big Canadian camp at Shorncliffe.

Ah, but all is not well with Ernie.

He was suffering, along with his physical wounds, from shell shock.

Undiagnosed.

He was so unobtrusive by nature, no one seems to have noticed how badly he was struggling. “I had always found Private Savatard to be a very quiet man and never gave any trouble,” said his friend later.

After five months of depot duty, they were perhaps starting to think about sending him back to France when, on 26th April 1917, there were some grenade explosions at Shorncliffe camp during a training exercise.

Though again, no one noticed, these explosions shook Ernie to the core and were perhaps the final straw.

He kept his own counsel and made a plan.

Just before 12am that night, with his mates snoring in the barracks’ dormitory on either side of him, he reached for his shaving kit and cut his own throat.

A doctor was called but the wound was five inches long, stretching round from his left ear, as he had been right-handed.

That truly must have taken some courage.

A week later, an inquest held at the Camp decided that Ernie had committed suicide, being of unsound mind at the time, due to a state of nervous collapse resulting from shell shock and injuries received on active service overseas.

The presiding Officer unusually made his empathy clear with the final verdict: “He was not to blame.”

And so they buried Ernie, who’d given all he had to give, in the most peaceful of picturesque places at Shorncliffe’s military cemetery, overlooking the Channel where we can only fervently hope, he found the peace he needed at last.

Comments