Walter Stenson, the lacemaking Stoker

- Claire Jordan

- Sep 17, 2023

- 4 min read

When 38 year old Walter Stenson finally arrived on his first ship, his first active posting after more than a year of training, he must have thought determinedly: right then, let’s get on with this and get it over with.

He had been sent on 31st August 1918 to the shiny HMS Glatton, a ship requisitioned from the Royal Norwegian Navy at the beginning of the War, but only now after much refitting and refurbishment, about to be sent into action.

On 11th September, she finally sailed for Dover and Walter was at last going to War.

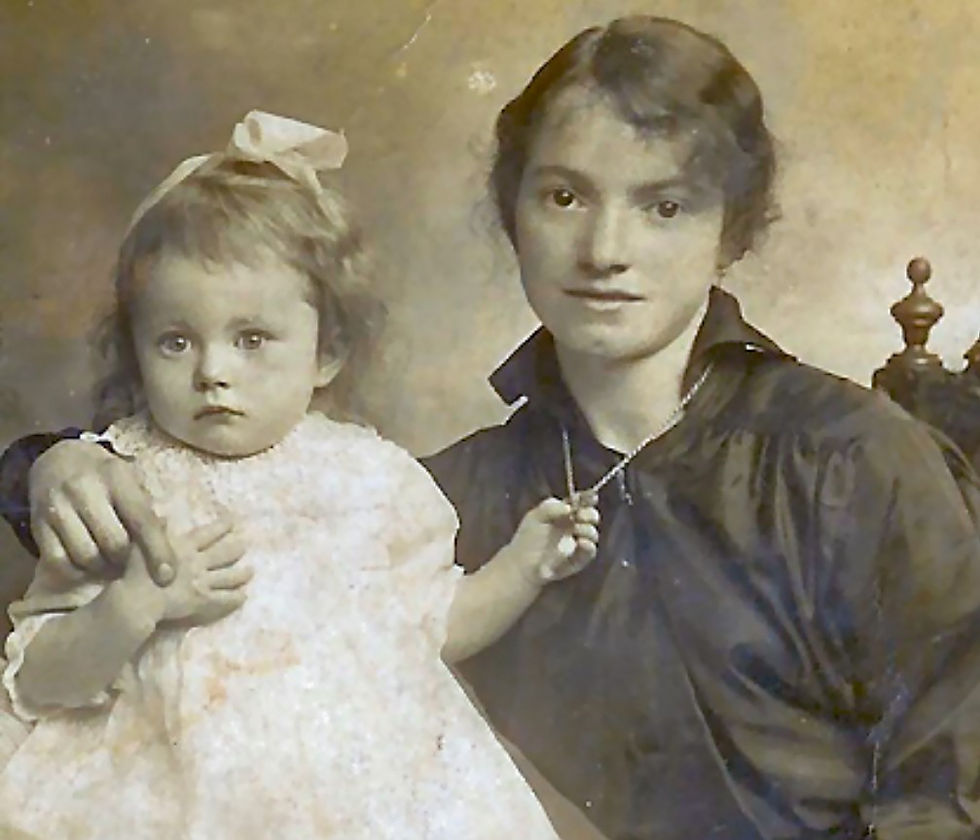

Like his father and mother before him, only-child Walter had been a professional lacemaker his whole life; he’d married Pauline Alice in 1902 and they had a little girl in 1909.

A rural village lacemaker turned Royal Navy Stoker would seem to make no sense but Walter, bless him, stood only 5’ 2½” tall and a tall Stoker would be semi-permanently concussed. Still, as an older chap, his arms unadorned by the usual maritime ink, he must have stood out.

Perhaps he even (on the quiet) kept a small handkerchief made by his Mum or Dad for him years ago in his pocket as a lucky talisman, something he firmly intended none of his crewmates should ever find out about.

But it could not keep him safe.

On the evening of 16th September 1918, Glatton was anchored in Dover’s busy wartime harbour preparing for her first offensive mission when something went terribly wrong.

At first, there was a small explosion, the cause of which is still unclear, in her midship magazine, which ignited the cordite stores nearby. Volcanic flames blew the roof off the Q turret and started to spread.

On the White Cliffs above the town, Glatton’s Captain had been walking with a Vice Admiral when they heard the explosion and rushed down to the harbour.

Finding his ship ablaze, the Captain first ordered the seacocks to be opened, hoping to flood the other magazines and prevent further blasts; this worked for the forward magazines, but the ones in the rear were now unreachable beyond a wall of flames.

Worse still, only 150 yards away from the burning Glatton, the heavily-laden ammunition ship Gransha lay at anchor with a panicking crew.

If Glatton’s flames reached the Gransha, Dover itself would be obliterated.

Now aboard the destroyer Cossack, the Vice Admiral ordered her to torpedo Glatton, again trying to flood the rear magazines before they ignited, but Cossack was too close to her stricken target and only a small hole was eventually made in her hull.

Glatton was still afloat, still burning.

A second destroyer, Myngs, was now ordered to torpedo Glatton’s starboard side, where Cossack had managed to make the small hole.

Finally it worked; agonisingly, Glatton capsized until at last the flames were extinguished, the screams of burning men quietened and a thousand held-breaths were let go.

As bad as it was, it was so nearly worse, but the toll was nevertheless awful: 60 men had been killed outright, with 124 horribly injured, 19 of whom died in the following hours of their burns.

It’s impossible to know at what point in that inferno the gentle lacemaker from a Derbyshire village perished.

And it’s very hard to imagine the horror of the situation for those who survived the initial blast, but who now had to fight both the flames engulfing them, and the realisation that they were being repeatedly torpedoed by our own ships at point-blank range, in the frantic attempt to prevent a much larger disaster.

Whatever their height, to me, Stokers are gigantically brave men; they have to endure not only the physical exigencies of the job, endlessly shovelling coal into their ships’ hellish furnaces, but also the psychological pressure exerted by the knowledge that, if anything should go wrong – a torpedo – a mine – they would stand next-to-no chance of getting up and out.

Walter’s widow Pauline back home in Draycott with their little girl Phyllis Annie eventually remarried, in 1924, to a former soldier named Frank Winson. He had been a Sherwood Forester during the War and taken prisoner, wounded in the arm by shrapnel splinters, on the first day of the Kaiserschlacht in March 1918. By the time Walter was first climbing aboard the ship which would shortly become his tomb at the end of August, Frank was just arriving home in England, having been repatriated on medical grounds by his captors.

Perhaps Frank’s hospital ship even unknowingly passed Walter’s Glatton in the harbour.

The fortunes of War.

The poor wreck of the Glatton remained for years in the middle of Dover harbour, visible at low-tide; it was an extraordinary task to move her as she was too heavy to simply be lifted. Eventually, she was shifted in 1926, after her many rents and tears were sealed underwater and her hull pumped full of air.

She was hauled to a gully by the old west pier, and remains there still, buried now underneath the car ferry terminal car park.

So please, next time you catch a ferry from Dover, tread softly and let Walter Stenson know he’s Not Forgotten.

Above: the beautiful CWGC Admiralty section at Woodlands Cemetery, Gillingham, Kent, site of the HMS Glatton Memorial below.

Comments