Unbreakable Beamish

- Claire Jordan

- Apr 19, 2022

- 3 min read

On 30th April 1942, the little mining village of Beamish, County Durham was as it had always been.

Formerly known as Pit Hill, it retained some admirably colourful local names; surrounded by Hell Hole Wood, Beamish also has the little street by the railway embankment called Peggy’s Wicket (although no one remembers why), and the hamlet of No Place to the south.

But by the end of the following day, 1st May 1942, everything had changed.

At almost 3am that morning, a Luftwaffe bomber on their way to destroy Durham Cathedral had become lost in the fog of the early summer small hours and was looking for somewhere to drop its bombs instead.

Perhaps catching the glint of the railway line which served the colliery, he let loose three 1000lb bombs on the little village.

The first exploded on impact and damaging some shops and houses on Station Road and catapulting everybody out of bed.

The second was fitted with a time-delay fuse of 6 hours and had very obviously fallen onto the railway embankment but not exploded.

No one knew if it had failed to explode as the first bomb had exploded, or if it would go off any moment now.

The footbridge, the Post Office and nearby houses were all roped off and the residents were evacuated. A Bomb Disposal team was called first thing the next morning, but they were delayed at a level crossing; had they not been, they would have gone up with the bomb when its delayed fuse triggered the explosion.

As it was, part of the railway was churned up, the footbridge damaged, a water main fractured, and the houses and shops hurt by the first bomb sustained further injury.

All of this caused great excitement in the local area and all that day, people came to Beamish from miles around to see what had happened, to check on friends and to hear everybody’s near-miss stories from the sleepless night before.

What none of them knew was that a third 1000lb bomb had fallen unseen into another building.

The hole it made in the roof was assumed to be damage from the two explosions earlier in the day.

The people of the village and the surrounding area, believing the emergency had passed, spent the day salvaging what they could from the damaged buildings and making sure everyone had somewhere to stay that night.

Approaching dusk on 1st May, people were lined up at the village bus stop waiting for the bus home. Children, full of excitement at the brush with Hitler on their doorstep, were still playing in the streets in the evening summer light, exploring piles of rubble. Two Special Constables in their early sixties were close by, trying to keep them from falling into holes and away from unsafe walls.

And then just after 9pm, the timer on the last bomb’s fuse, buried for 18 hours in the foundations of a village shop, told the device to explode.

The blast ripped across the road to the people waiting at the bus stop. It uprooted trees.

Fragments of stone and glass and people filled the air.

Special Constable Sam Edgell’s son Jack knew his Dad was on duty and rocketed out of their house towards the scene; he found his father laying twisted in the road, unconscious but alive, his boots blown off his feet.

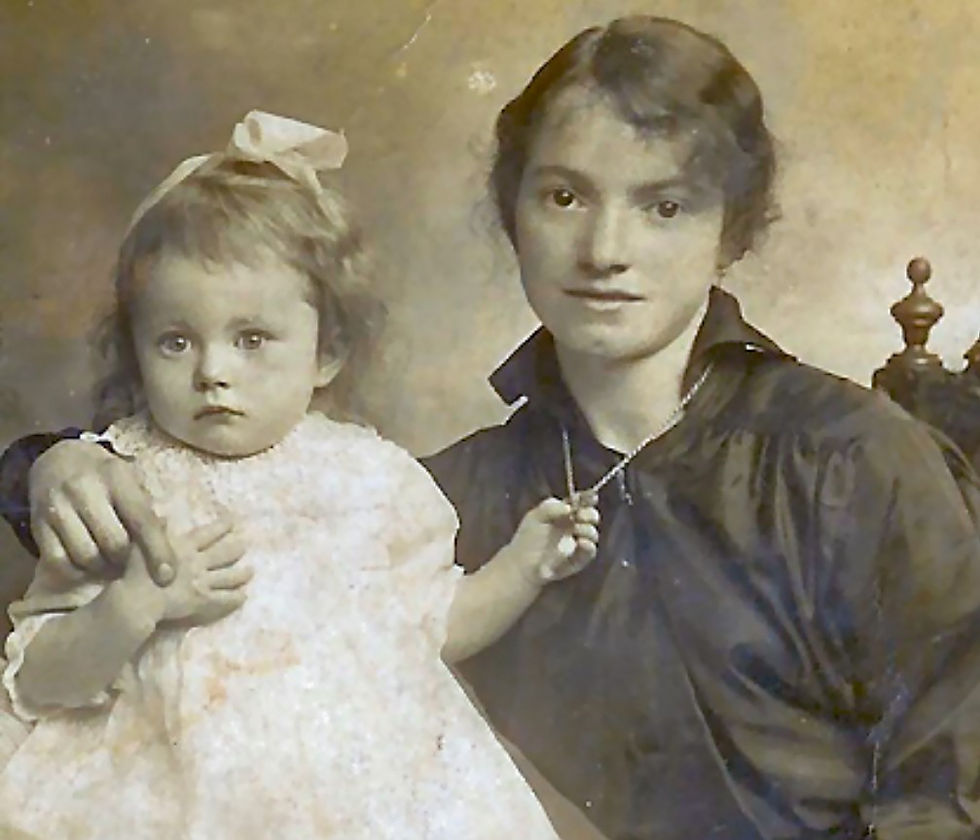

People searched frantically in the chaos, screaming for their children. Miners from the colliery were reduced to tears as they unearthed two small broken bodies, 9 year old Clive Lawson and 8 year old Irene Seymour. She had been hand in hand at the moment of the blast with her 77 year old grandmother Mathilda, who lay badly injured close by, and would soon die of her injuries.

17 year old Gwennie Hannant had been to the pictures with her boyfriend Jim that evening; his call-up papers had just arrived and were in his pocket. Next to him at the moment the 1000lb of explosives detonated, Gwennie was killed outright by the blast; Jim survived it with two broken legs.

Ten year old Sylvia Spence had been with her mother Elizabeth; both were found terribly injured and both would die soon afterwards.

Special Constable Robert Reay was found dead in the ruins of the nearby house he had been helping to repair. His colleague, Jack’s Dad Special Constable Sam Edgell, would not survive his injuries.

Seven others were seriously injured and a further 28 were also casualties.

Hitler tried, as Winston put it, to break us in our island, to break our spirit, but even on an unimaginable night like this in a tiny brave County Durham pit village, he never managed it.

Comments