Tontine Street, Folkestone

- Claire Jordan

- May 23, 2023

- 3 min read

I’ve always been quietly proud of Folkestone, the ancient little fishing town on the south coast and here’s one of the reasons why.

On the balmy late-spring evening of Friday 25th May 1917, the shops in the little town were staying busy later because it was a Bank Holiday weekend, and people were keen to gather up what goodies could be had.

Stokes the grocers on Tontine Street was doing a roaring trade at about 6.20pm when bangs were heard in the distance coming not from the sea but from inland.

Young mums with small children and their elderly grannies were unfazed. Early in the War, seaside towns along the east coast had been ignominiously shelled by the German High Seas Fleet, but the Royal Navy had soon put a stop to that and since the Zeppelin threat had receded, there was no reason to think there was any danger from above. Folkestone itself had no air-raid defences, no sirens.

It was probably gun practice up at the big Canadian Army Camp at Shorncliffe.

What no-one knew was that the enemy had a new long-range fleet of bomber aircraft that could reach England and they were keen to try them out.

Today was the day. The first ever airplane attack on England.

The new twin-engine enemy Gotha bombers had launched a raid against London earlier that Friday but, hampered by low cloud over the capital, had instead turned south-east, following the main railway line down the Medway valley, then heading south towards the coast.

Folkestone lay helplessly underneath them, and 21 planes now unleashed hell.

The Army Camp took the first bombs.

One exploded on a tent between two huts in Howitzer Lines, killing eleven young men about to set out on a route march; another landed on Risborough Field, killing four Canadian gunners and an American serving with them as they put up a tent. A British soldier was killed in a quarantine hut and another Canadian died when he was hit full-square by an unexploded bomb on the Cavalry Drill Ground.

The Gotha G-IVs were also equipped with machine guns which inflicted further devastation on the camp. It was chaos.

Eighteen soldiers and numerous horses were killed at Shorncliffe and at least ninety men further wounded; many had only just arrived from Canada, eager to join the fight.

Knowing nothing of this horror, down in the town, the queue on Tontine Street for the grocer’s shop was moving along cheerfully in the early evening sunshine.

William Stokes, the owner, and his son Arthur aged 14 were busy serving their regular customers.

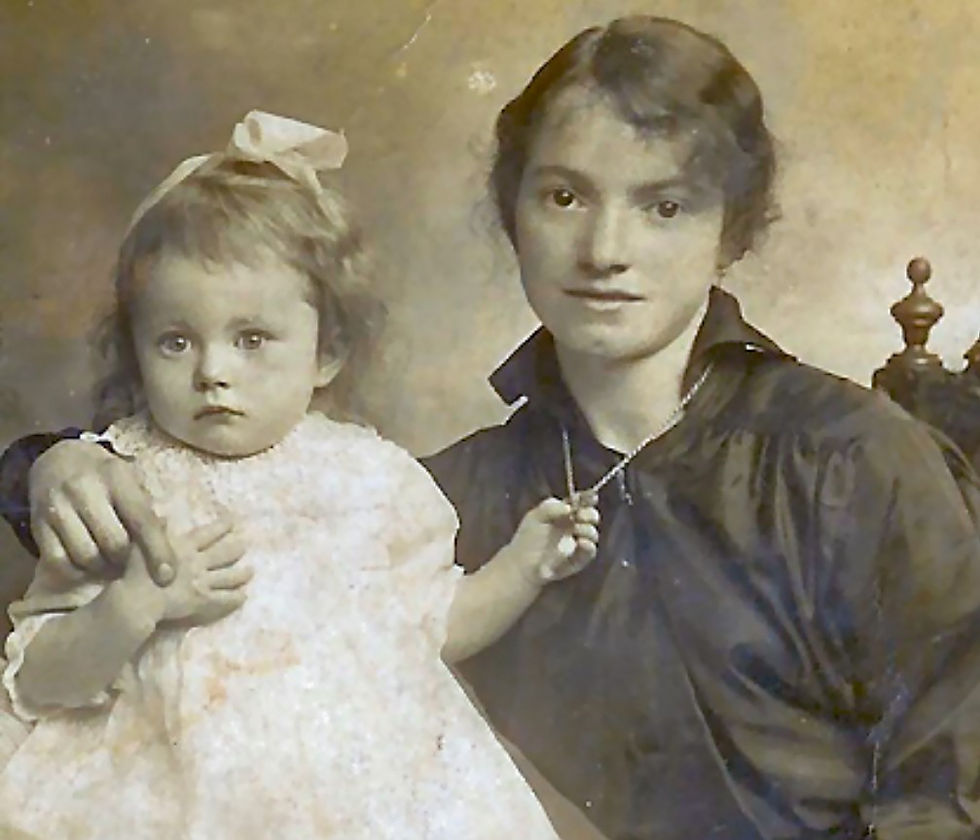

17-year-old book-keepers Florrie Rumsey (above) and Edie Eales were both still at their desks.

Waiting patiently out on Tontine Street were 2-month-old Walter Moss with his Mum and nearby were ten-month-old William Norris with him big sister Florence (aged 2) with their Mother.

Then out of nowhere came a loud bang, and a bright light, and a searing heat, as a single bomb fell onto the queue in the street outside the grocer’s shop.

Walter and William the babies, their mothers and siblings, the Stokes boys, Florrie and Edie the book-keeping girls, all were dead or dying, as a ruptured gas-main caught light and the air turned into fire.

Sixty people died in that moment on Tontine Street.

Mr Stokes, the grocer, had actually only popped back to the shop that evening to help with the queue because his wife hadn’t quite managed to put his tea on the table at the usual time that day and she would be racked with guilt about it to the end of her days.

Reports vary but it was eventually determined that a total of 71 civilians were killed in the vicinity of the town: 16 men, 28 women and 27 children. The official number injured was 96 but many of these injuries were life-changing or would eventually prove fatal.

Walter Moss, the eight-week-old baby who was hit in the chest by shrapnel, and his mother Jane, whose legs were ripped away in the blast, were the family of Private George Moss, a Canadian soldier and stalwart of the Salvation Army, who’d wanted to become a chaplain; by the end of the War, George had lost four brothers, a cousin, his father-in-law as well as his wife and baby son.

There were so many local families with the heart ripped out of them. The little town was in shock and would mourn for many years to come.

But Stokes the grocers and Gosnold’s the drapers, which was also destroyed by the Tontine Street bomb, were both rebuilt and open again for business within a month or two that summer and customers flocked back to the plucky stores, even the families of those who had died there.

Everyone was determined to prove they would not be broken, even under grief of this magnitude.

Lest We Forget.

Soldiers carry Walter Moss's little coffin

Comments