The Fete Fire

- Claire Jordan

- Jul 11, 2023

- 5 min read

Ok, stick with me on this one.

For many years at Gillingham, Kent, the high point of the summer for the people of the naval town was the annual summer fete.

It was good solid family fun with stalls and games and music and bunting, and it also acted as an important fundraiser for the local hospital, St Bartholemew’s, in the days before the NHS. The town’s Fire Brigade was always involved, as were St John’s Ambulance, the Naval Cadets and the Sea Scouts.

The fete would last for several days, culminating on the final day with a mock wedding ceremony, featuring two firemen dressed as the bride and groom who would circulate the crowds in the park through the day, shaking buckets for donations, shaking hands, before the staging of a big pretend wedding reception at the end of the day.

The whole idea of the Fireman’s Wedding perhaps sounds strange now, but it was a common showpiece of many park fetes at the time, especially in London.

For the finale, a makeshift three storey tower made 30 to 40 ft high out of lashed-together timber covered in tarpaulin would act as the venue for the wedding reception. The ‘guests’ were played by the young Cadets and Scouts, their parents and younger brothers and sisters watching proudly on.

The idea was for the makeshift house to pretend-catch fire, simulated by lots of purposely-generated smoke, at which point the Fire Brigade would swoop in, put out the ‘fire’ and save all the wedding guests, along with their colleagues dressed as the newlyweds, from the not-really-burning edifice. A happy ending, with everyone clapping and cheering.

In the 1920s, it was a well-established and joyful event for local families in the town, celebrating the skill and courage of the Fire Brigade, many of whom had served through the First World War at sea themselves. Their own families came to the fete to watch Dad take part in the show.

In 1929, the final day of the fete in Gillingham Park was Thursday 11th July.

At about 10pm, the Fireman’s Wedding was in full swing, and so when flames burst out of the tinder-dry first floor of the temporary wooden house, the crowd laughed and cheered and applauded, thinking it was part of the show.

But something had gone wrong.

Young Cadets and Scouts, pretend wedding guests, were instantly trapped inside the structure as the tarp ignited around them. They began to shout for help, but Mums and Dads watching on amid the noise and hoopla thought it was all for good effect.

But six year old Molly Cheeseman, whose big brother Eric was a Naval Cadet inside the house, could see the truth. ‘Eric’s burning!’ she began to scream, ‘Eric’s burning!’

The crowd quietened, uncertain. The music stopped. Then more screams rang out as a figure leapt from the burning tower.

Somehow, inconceivably, the horror was now real.

Olive Searles could only watch on as her ten year old son Leonard threw his arms over his head and became engulfed by the flames. Lottie Brunning saw her only child, David, perish in the same way. Mabel Mitchell and her five year old daughter Vera watched Vera’s Dad Royal jump from the burning structure and run, his clothes and hair on fire, to a water trough. He died 36 hours later; Mabel never left his side.

13 year old Leonard Winn’s dad Gordon wasn’t present when he heard what was happening: “I raced to the scene of the fete in my car. My little boy, his clothes burnt and still smouldering, lay on the ground. The poor little fellow could hardly see. He was terribly burned. I lifted him gently and placed him in my car, then raced along the road to the hospital. All through the night I sat by his bed side. He was so brave - oh so brave."

In the terrible following hours, all that burned and blinded Leonard could think about were his friends: “Dad, how are the other boys?’ he kept asking, ‘did they get away?’ He died at dawn the next morning.

Fireman John Tabrett had been part of the show earlier on and ran back into the burning structure to try to save the screaming boys. Fireman Francis Cokayne could have gotten out, but chose instead, with John Tabrett, to try to reach the trapped children. Francis was seen jumping from one of the flaming floors with a child tucked under his arm, but he did not survive.

Despite the heroic efforts of the emergency services present and many members of the public, fifteen people died that day or in the following hours, nine of them Scouts and Cadets.

They are: Scout Reg Barret (13), Cadet David Brunning (12), Cadet Eric Cheeseman (12), Les Neale (13), Cadet Leonard Searles (10), Cadet & Scout Ivor Sinden (11), Scout William Spinks (13), Robert Usher (14), Scout Leonard Winn (13), Fireman Francis Cokayne (52), Royal Mitchell (37), Fireman Albert Nicholls (56), Fireman Arthur John Tabrett (45), Petty Officer John Nutton (37) and Fred Worrall (30).

In the following days, a dozen of the Fete Fire’s victims were buried in a row at nearby Woodlands Cemetery.

Two of the men, Albert Nicholls and John Nutton, are buried in the Admiralty plot there and are looked after therefore by the CWGC. John Nutton had made it right the way through the War as a Royal Navy steward.

And Albert Nicholls’ son Horace had joined the Navy during the War but had died aged 17 of meningitis, so after Albert’s death in the Fete Fire twelve years later, he was buried in the same Admiralty grave as his boy, though never himself added to the headstone, so you wouldn’t know this brave man was there. Somehow, even in death, Albert is putting others before himself.

Leonard Searles has no marked grave; his family buried him with his little sister Winnie, who’d died some years earlier, up by the cemetery chapel. If you ever go and sit quietly near the spot, you’ll see the local squirrels seem especially to like Len and Winnie’s grassy spot.

For many years, there was no plaque or marker but in 2011, a memorial was finally put up in nearby Gillingham Park where the disaster took place. It is a double-sided silhouette of a little boy and a fireman leaning against a panel featuring the names of the lost.

Like so many of the War stories I post, this is a terribly sad and truly horrifying tale, but it is also shot through with the same sort of courage and selflessness which made those lads climb up out of the trenches when the whistles blew and which must equally never be forgotten.

Had the young Sea Scouts and Naval Cadets lived, they would likely have been called on to fight the Second World War for us too.

Lest We Forget, we are all standing now on the shoulders of giants, little ones included.

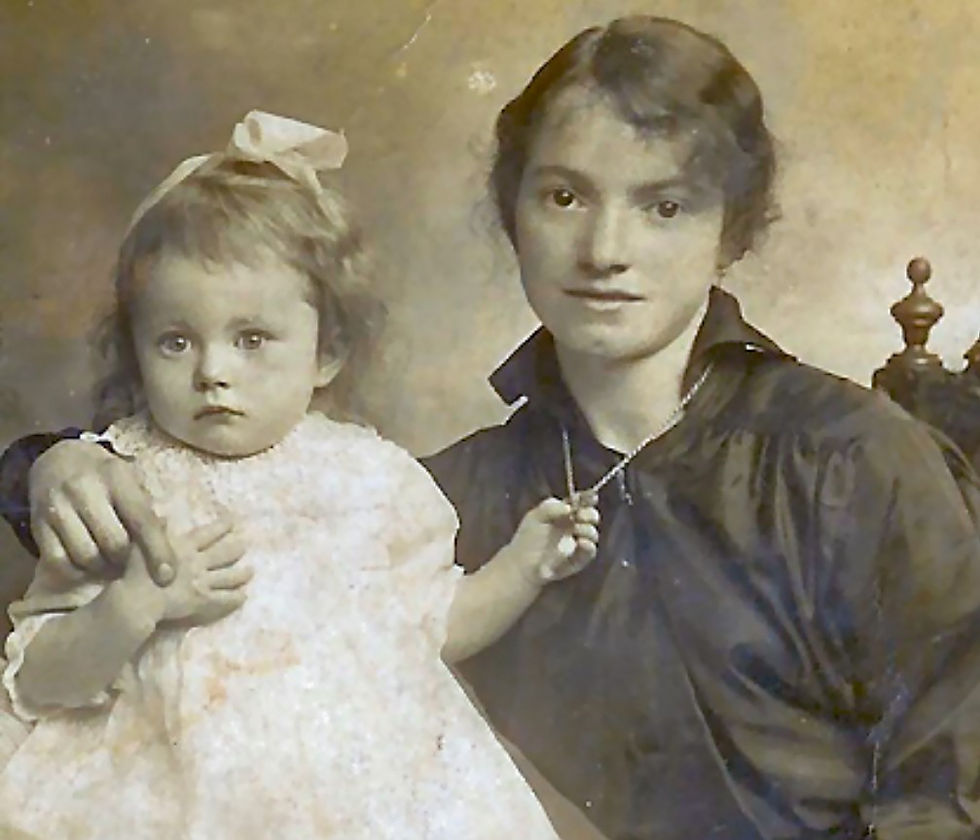

(The above image is a detail from the very beautiful 1884 painting ‘Inconsolable Grief’, by Ivan Kramskoi, at the Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Ivan has painted his wife, after the loss of their two sons.)

Comments