"The Best Souvenir to Take Home is One's Head"

- Claire Jordan

- Apr 19, 2022

- 3 min read

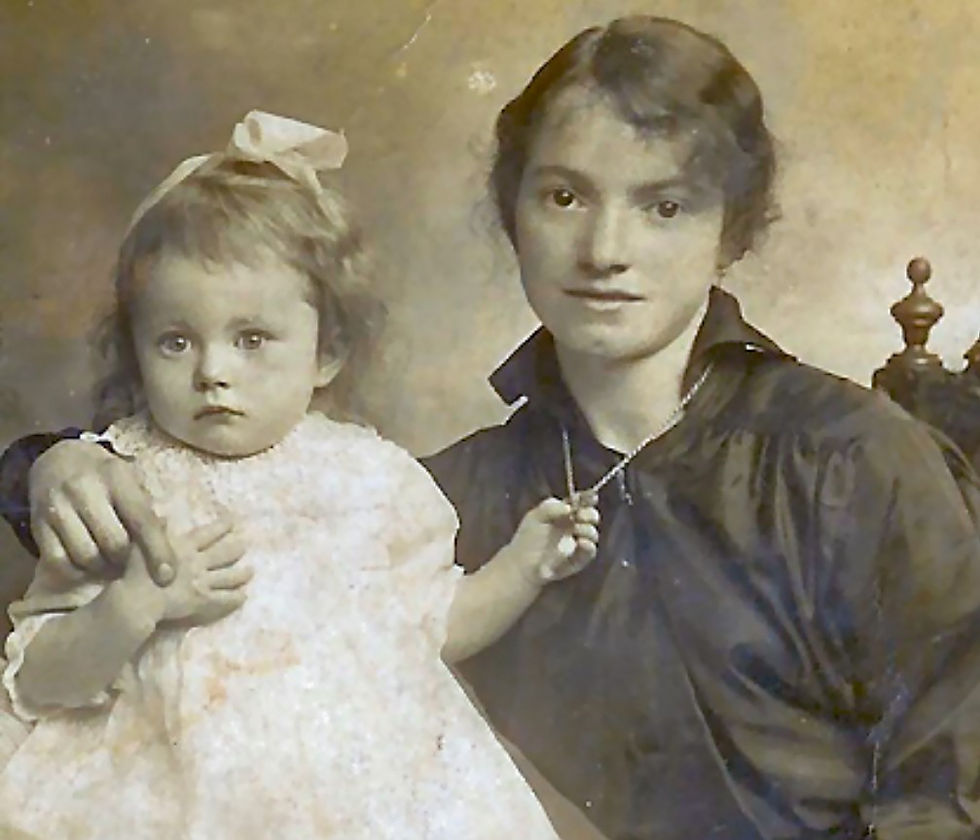

Here are brave brothers Alfred Percy (known as Percy) (above) and William Dandridge (below).

Their father was a successful metal merchant and the boys lived for much of their childhood in a beautiful big house on Albemarle Road in Beckenham, south-east London (a house which would be destroyed during WW2 by a V1 which fell onto the road in the small hours of 2nd July 1944.)

Their father married their Mum Catherine in 1881 and seven children swiftly followed – early to arrive were twin boys who would be Percy and Harold, but poor Catherine died, quite possibly in childbirth, when her youngest was still in nappies.

Percy (with his twin) was the eldest Dandridge sons and William would be the littlest. Dad Alfred’s success in business meant that he could afford to employ a small army of servants and nannies to help bring up his motherless children when they were still small, and then to send them off to Sherborne School in Dorset when they were old enough, where it seems they all thrived.

Percy was a beautiful pianist but William’s talent lay in the field of medicine. He gained a medical degree from Cambridge and when the War came, he was made a Lieutenant in the Royal Army Medical Corps.

Percy elected to serve with the men, despite his more privileged background, and wrote home lyrical letters from the Front, where he fought the early weeks of the Battle of the Somme in July 1916 as a Lance Corporal with the 20th King’s Royal Rifle Corps.

“The best souvenir to take home,” wrote Percy, “is one's head.

It is not easy to get accustomed to the din and clatter of bursting bombs, popping machine guns, sizzling shrapnel, ping of rifle bullets and explosion of trench mortars. To see a company of soldiers rigged out in gas helmets is enough to boggle the imagination. We have our cheery times with many a concert, with songs, ballads, choruses and recitations.

Pack up Your Troubles in Your Old Kit Bag goes very well until Fritz find the top of the dugout with his shell when one's smile changes to an anxious look of who can get out first before it all collapses.

Life up near the line is of continual excitement, daily air attacks, artillery duels, attacks and counter attacks but overall there is a longing for peace, which our enemies must wish for even more than we do.”

But his cheerful luck wouldn’t hold out. On 25th July, Percy was part of a working party in the Montauban sector trying to maintain communications wire which was constantly being destroyed when the enemy began a heavy rain of shellfire onto his position.

He was wounded, though it is not clear quite how.

He held on for two weeks, losing his fight finally in a hospital at Abbeville, where he was buried in the Communal Cemetery.

In fact, according to his baptismal register, he was born on 6th August 1887, which means he died of his wounds on his 29th birthday.

‘A Dearly Loved Son and Brother,’ reads his headstone, ‘and a Charming Friend.’

Meanwhile, youngest brother and medical doctor William was still in the fight and made it almost to the end.

On 5th October 1918, William was the officer accompanying a party of stretcher bearers out on a mission to bring in the wounded up near Ypres when he was hit, dying the same day in a field hospital at Haringhe.

Brave brothers, you are still dearly loved and never forgottAboveen.

Comments