Reggie

- Claire Jordan

- Apr 18, 2022

- 4 min read

Years ago, I went to a friend’s wedding, the reception of which was at the Salomans Estate in Tunbridge Wells. I didn’t know who David Salomans was then, to my shame, but I do now and he’s definitely someone worth knowing.

The #RoyalEngineers 1/3rd Kent Fortress Company was a part-time Territorial Force unit raised almost entirely around the close-knit little town of Tunbridge Wells.

In exchange for one evening and maybe a Saturday afternoon a week and a bit of marching about, the Territorials offered hard-working young shop assistants and office clerks the chance to learn some new skills, have a bit of craic with their mates and put a few extra pennies in their pockets.

Best of all, they got a two-week paid holiday every summer in the form of the mandatory annual training camp.

The men of the Tunbridge Wells 1/3rd Kent Fortress Company lived on the same roads, worked in the same places, drank in the same pubs. Many had been to school together. Their girlfriends and sisters were friends.

So when War came in August 1914 and all the Territorial units were mobilised, it must have been some comfort that, if they were going off on this big adventure, they were at least all going together. A few Regulars were drafted into the Company too, old soldiers who could help keep lads in line.

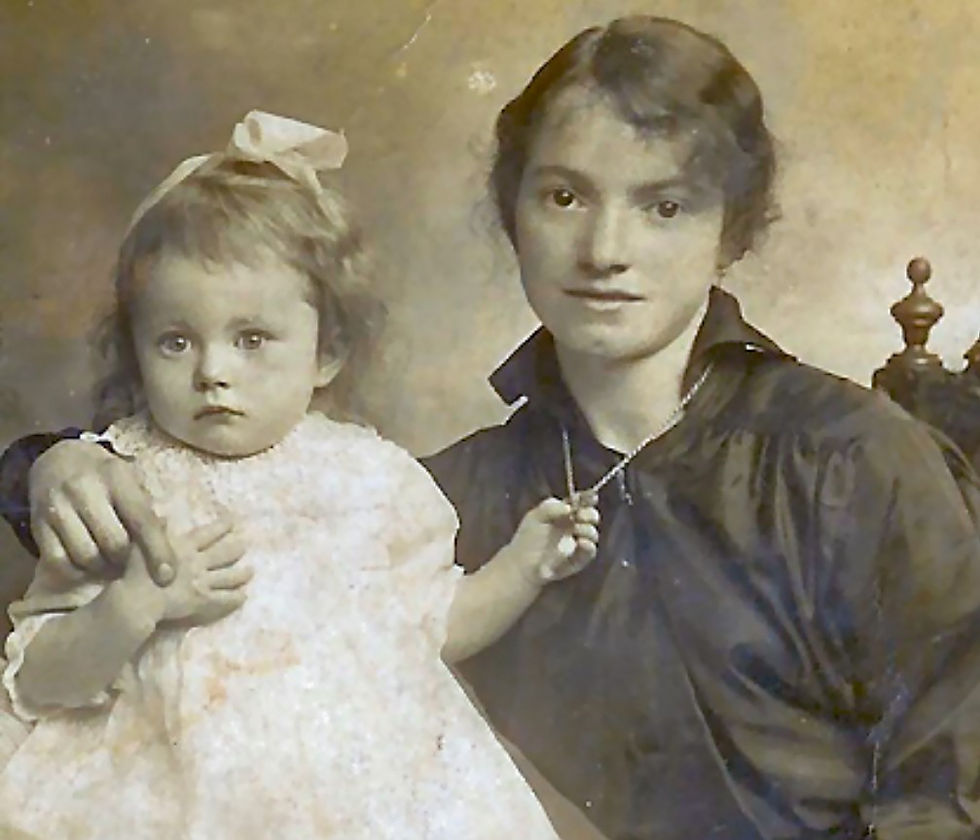

When, after more than a year’s full-time training, they embarked for overseas service on 12th October 1915, their Company Commander was David Reginald Salomans (known as Reggie), the only son and heir of the local Justice of the Peace, barrister and scientific author of the same name.

About 4pm on 28th October, the men were loaded onto HMS Hythe, a little converted cross-Channel ferry, and the little ship set sail from Mudros, heading for the rumbling horrors of the Gallipoli peninsula. She was terribly overloaded, the men crowded onto the decks, practically standing room only.

The seas were rough and squally; it was a nervy, uncomfortable sailing. Men tried their best to fight down nausea, whether it was seasickness or apprehension they perhaps could not have said themselves. Their big moment was finally here.

Around 8pm as the Hythe approached the murderous shoreline, all her lights had been put out to avoid attracting the enemy’s guns. Bumping along the sides were the terrible carcasses of dead donkeys and mules, killed by shrapnel and shell, and towed out to sea because it was impossible to bury them, their bodies floating helplessly, constantly, back towards the shore with the tide.

And this was the moment the Hythe collided in the stinking darkness of the Aegean night with a much large troopship.

The heavier ship had ploughed into the little ferry, forward of the bridge, scything her practically in half, sealing her fate.

A warning whistle gave almost no warning; there was no time. Suddenly all was panic and chaos in the darkness as the soldiers and the crew desperately tried to launch lifeboats, the decks tipping treacherously under their feet, wounded men scrambling for lifejackets, yelling for help.

In the middle of it all was Reggie Salomans, fighting the battle of his life with the sea and with the elements for the lives of his men.

The Hythe’s captain, knowing his ship was doomed, yelled at Reggie Salomans: “Come on, jump! This is your last chance! I’m going now.”

But Reggie was going nowhere. “No, I will see my men safe first,” he shouted back.

He and his Company Sergeant Major John Carter were on the bridge, rallying, exhorting their lads to keep calm, to get clear, to swim, to keep going, trying to launch another lifeboat for them, when the boards on which they stood slipped beneath the churning waters and they were both swallowed up.

Reggie had been wearing the state-of-the-art lifejacket his Dad had equipped him with, but he had torn it off to give to one of his men who did not have one.

Fred Mills was one of the lucky ones who survived the sinking and spoke with great emotion of Captain Salomans at the subsequent enquiry: “It is my own opinion if he had have thought of himself first, he would have been saved, and if I am right, he died a hero’s death and we honour him.”

Among the boys he fought in vain to save were teenaged brothers Alfred and Harry Funnell, and their cousins 25 year old William and 22 year old Frank Funnell, both married with small children.

There was Fred Somers, age 37, who had served fifteen years earlier in the Boer War and had worked in Tunbridge Wells since he left the Army as a plumber and volunteer fireman.

21 year old Tom Godsmark could see what was happening, but wouldn’t leave the horses aboard the Hythe in his care. They were terrified and would not survive this, and he would not leave them.

Tom Handley, aged 19, worked at the Co-Op in Tunbridge Wells; he was now following his Dad, who had died serving in the Boer War in 1900.

Harry Goldbaum was only 17 on the day the Hythe sank underneath him. He was too young to go but he’d wangled his place on board because another underaged lad’s Mum had banned her boy from going. Harry worked on the Salomans Estate, but his parents lived in Stepney and so by the time they realised what he’d done, it was too late to stop him.

On 28th October 1915, 154 men died when the Hythe sank in view of Gallipoli where they were heading to fight, 129 of them were Sappers of the 1/3rd Kent Fortress Company.

So many of the lost men lived along Silverdale Road in High Broom that the postman delivering news of their deaths along the road was so overcome by the weight of heartbreak he was causing that he had to return to the depot. Someone else had to finish the round that day.

So, yes… if you are ever invited to a wedding at the Salomans Estate in Tunbridge Wells, you will doubtless have a lovely time with friends, but you will also be in truly heroic company.

Comments