Dukey

- Claire Jordan

- Apr 19, 2022

- 4 min read

The thing about the people for whom we wear poppies at this time of year is that they didn’t just have to do a Really Brave Thing once, in defence of their mates, their Mum, their children, their home, their honour.

If they survived one Brave Thing, they then had to keep on doing them until either they went down fighting, or the War was won.

Surely it’s one thing to do it once… to hop the bags when the whistles blow, to gather your little ones and the dog into the shelter when the sirens ratchet up and bombs scream down, to climb out of the landing craft and wade ashore, to jump out of the plane into a hail of flak, to keep shovelling coal into furnaces in the bowels of a ship desperately dodging torpedoes in a minefield, to scramble to your aircraft when the bell shrieks, to climb back into your patched-up bomber still ticking from last night’s raid…

It’s one thing to meet the moment head-on when it first comes.

But when you know now what’s coming because you’ve survived it once already and you have to make yourself do it again, and again, and again, because that is what is required of you, yeah, that is surely true courage.

These are all people whose names we don’t know but who ultimately bought us all our own real chance at life.

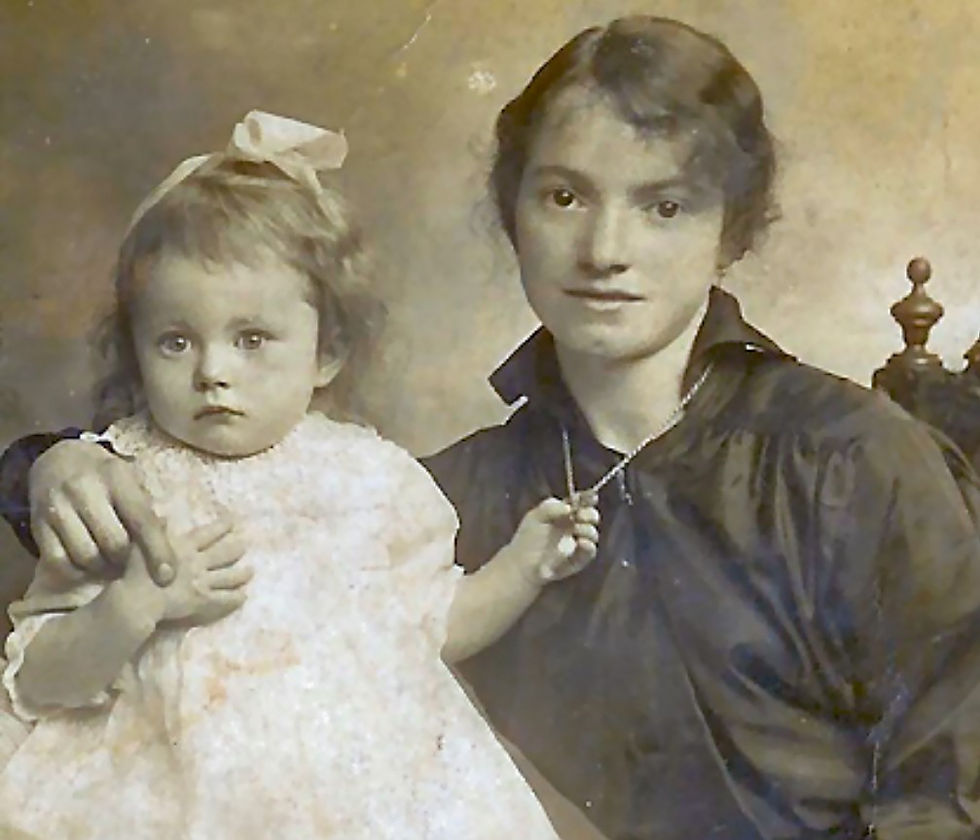

This is one such chap, and it's a name worth knowing: he is Sergeant Marmaduke Ridley, a 24 year old RAF Spitfire pilot from Benwell, Newcastle-upon-Tyne. His Mum’s name was Isabel.

Early in 1940, he had joined 616 Squadron at Leconfield and began with them to patrol Flamborough Head off the Yorkshire coast, but as the Germans swept in and France began to fall at the end of May, Dukey and his Squadron moved down to Rochford (now Southend Airport) in Essex, where they flew top cover over Dunkirk, trying to defend the evacuation from attack.

On 27th May over Dunkirk, Dukey was attacked by about thirty Messerschmitt 109s and in the brawl, he was wounded in the head, his Spitfire badly damaged, but he managed somehow to get himself back across the Channel to safety.

Patched up, he and the rest of 616 Squadron continued to defend the Dunkirk evacuation until 5th June, after which they were returned to night patrols in Yorkshire.

On 1st August, Dukey was scrambled for a convoy patrol, duelling with a fearsome Junkers 88 as he chased it out to sea, bullets destroying his radio set and engine bearer.

Again (somehow), he landed with his life.

Five days later, he was scrambled to meet another Junkers 88 which was chased off into the cloud, but all the Spitfires of 616 sent to meet that plane were hit by flying debris from the wounded enemy bomber.

Two weeks later, 616 Squadron was moved south again to RAF Kenley where, on 19th August, they were 14 Spitfires strong. Situation: dire.

Over the next days, with the Battle of Britain ramping up and the Luftwaffe sending over more and more fighters and bombers in the effort to break the back of RAF Fighter Command, 616 Squadron were flying multiple daily patrols, sustaining their first casualty when Pilot Officer “Cocky” Dundas was wounded and baled out after a fight with Messerschmitt 109s on 22nd August.

On 25th, they were scrambled to protect Maidstone and then sent to Canterbury to intercept a raid of about twenty Dornier 17 bombers, escorted by a further twenty Messerschmitts.

The Squadron was bounced (attacked from above, out of the sun) by the enemy fighters and the formation fractured. Dukey attacked and destroyed a Dornier and his fellow pilots despatched or damaged a further six enemy aircraft, but the Squadron lost Sgt Westmoreland killed that day, with Sgt Wareing also shot down.

By 26th August, with some serious gaps now in the Squadron’s pilots, Dukey and six other Spits were scrambled yet again to meet a Heinkel 111 medium bomber, which ultimately disappeared into cloud.

But now came intelligence that two raids of more than forty enemy aircraft were approaching, and Dukey and his mates had to stop them.

Worse, a large formation of enemy fighters was then reported above their bombers (which is exactly how you get bounced.)

616’s Blue Section formed a defensive circle and Yellow Section tried to join them but were blocked by Messerschmitts, which forced three Spitfires to ground with wounded pilots.

Now around noon, news arrived of more enemy aircraft approaching Dover and Deal, and Dukey and the other men of 616 Squadron still standing were sent coastwards to meet them.

But enemy fighters were waiting for them and the plucky Spitfires were bounced yet again.

And this would be the fight in which Marmaduke Ridley fell, along with a fellow Spitfire pilot, Sgt Moberly.

Dukey’s Spit crashed at Addisham, just south-east of Canterbury. Impossible to know if he was gone by the time he hit the ground or not.

He had faced down the high-likelihood of that moment so many times but bless him, here now it was in dreadful technicolour.

He was buried at Hawkinge Cemetery just above Folkestone, and will eternally stand as one of The Few.

Comments