Dearly Loved & Not Forgotten

- Claire Jordan

- Jun 18, 2023

- 2 min read

This year, today especially, I wanted also to put up a tribute for another tunneller who served in the same 254th Tunnelling Company as William Hackett VC (see last post) and would be lost almost a year later.

Jim Hooton was also an older man, a walling stonemason from Kendal.

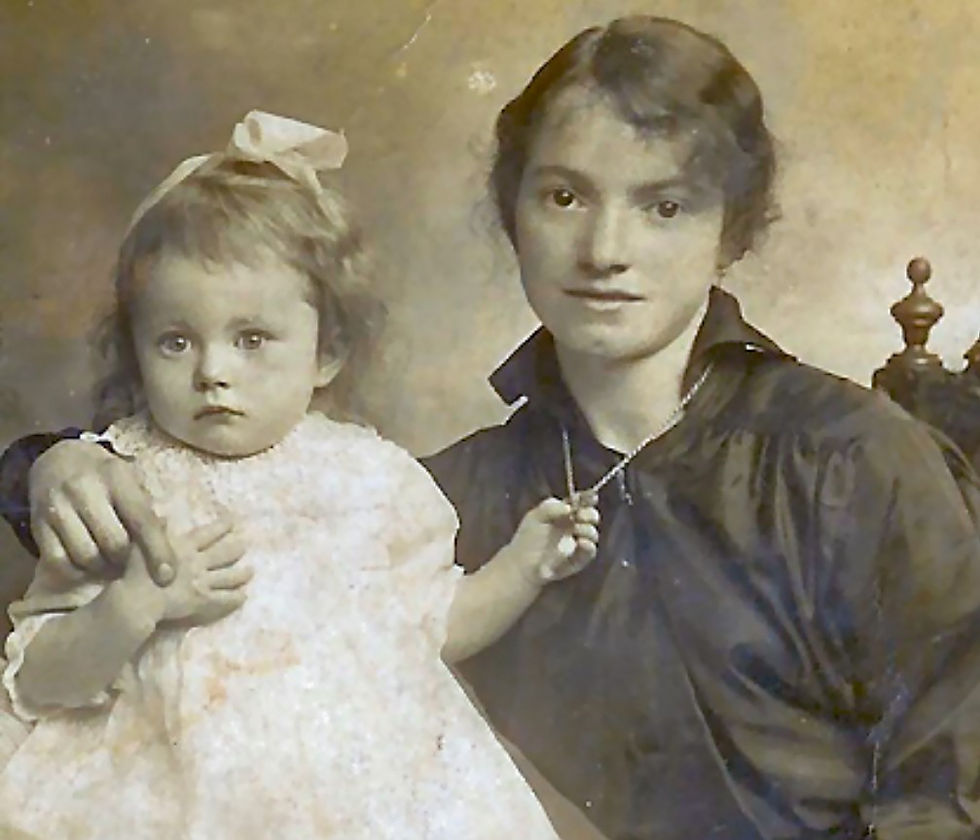

He’d married a young widow named Edith Annie on New Year’s Day 1906 and they’d welcomed a baby girl, also named Edith, in 1911, but bless her, she lived only a few weeks. There would be no more children for Jim and Edith Annie.

As away across the Channel, Sapper Hackett was beginning his last month in 1916, Jim Hooton was enlisting in his hometown. In the early spring of 1917, with prep for the massive offensive of the summer in full swing, Jim was rushed out to France to join Hackett’s old 254th Tunnelling Company.

From his papers, it is not clear quite how he was so grievously injured on 18th June.

It was not unknown for tunnellers to suddenly meet their enemy counterparts in the dark, cramped galleries under the churned French earth, when desperate hand-to-hand fighting would ensue.

Or perhaps topside, Jim’s position was strafed by a passing enemy aircraft as he climbed up out of the ground.

He may even have volunteered for an infantry raiding party, as courageous tunnellers needing literal change of air, sometimes did.

The war diary for his 254th Tunnelling Company for June 1917 is missing.

But however it happened, on 18th June 1917, Jim was brought to the 3rd Canadian Casualty Clearing Station at Lijssenthoek with gunshot wounds to the head, chest, right arm and hand.

As if he’d instinctively put out his arm to protect himself.

But his injuries were not survivable and he died later that day, aged 36.

Back home, Edith Annie was now a widow twice over, with no children to look after, and she came to London and volunteered six months after Jim’s death in France, to serve with the Queen Mary’s Auxiliary Army Corps, as Worker No.22747.

She was doing her own bit for the War effort, the QMAAC helping to fill some of the roles left empty by the men at the Front, things like store work, admin and catering.

After 14 months of service, Edith herself was worn out, discharged medically unfit from the QMAAC and given a Silver War Badge, to show she’d served, for her troubles.

After the War, Edith stayed on in south London, eventually marrying in 1936 for a third time in her mid-50s, to a younger man named Walter Dowsing; Walter had already been a soldier in the Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding) Regiment for seven years by the time the Great War came and, promoted Sergeant, was kept in India throughout.

Edith Annie went through a Second World War and all the horrors of the Blitz, with Walter, in Lambeth and died peacefully in her eighties in 1961.

“Dearly Loved,” she had had inscribed a lifetime ago on Jim’s headstone at Lijssenthoek (below), “and Not Forgotten.”

Comments